The Netherlands

UP2030 Horizon Europe

Intervention Design

Design & Research

6 months | 2025

The Spatial Justice Reflection Ecosystem is a graduation project developed with Citizen Voice (TU Delft) that strengthens how Dutch municipalities reflect on spatial justice alongside climate-neutral planning.

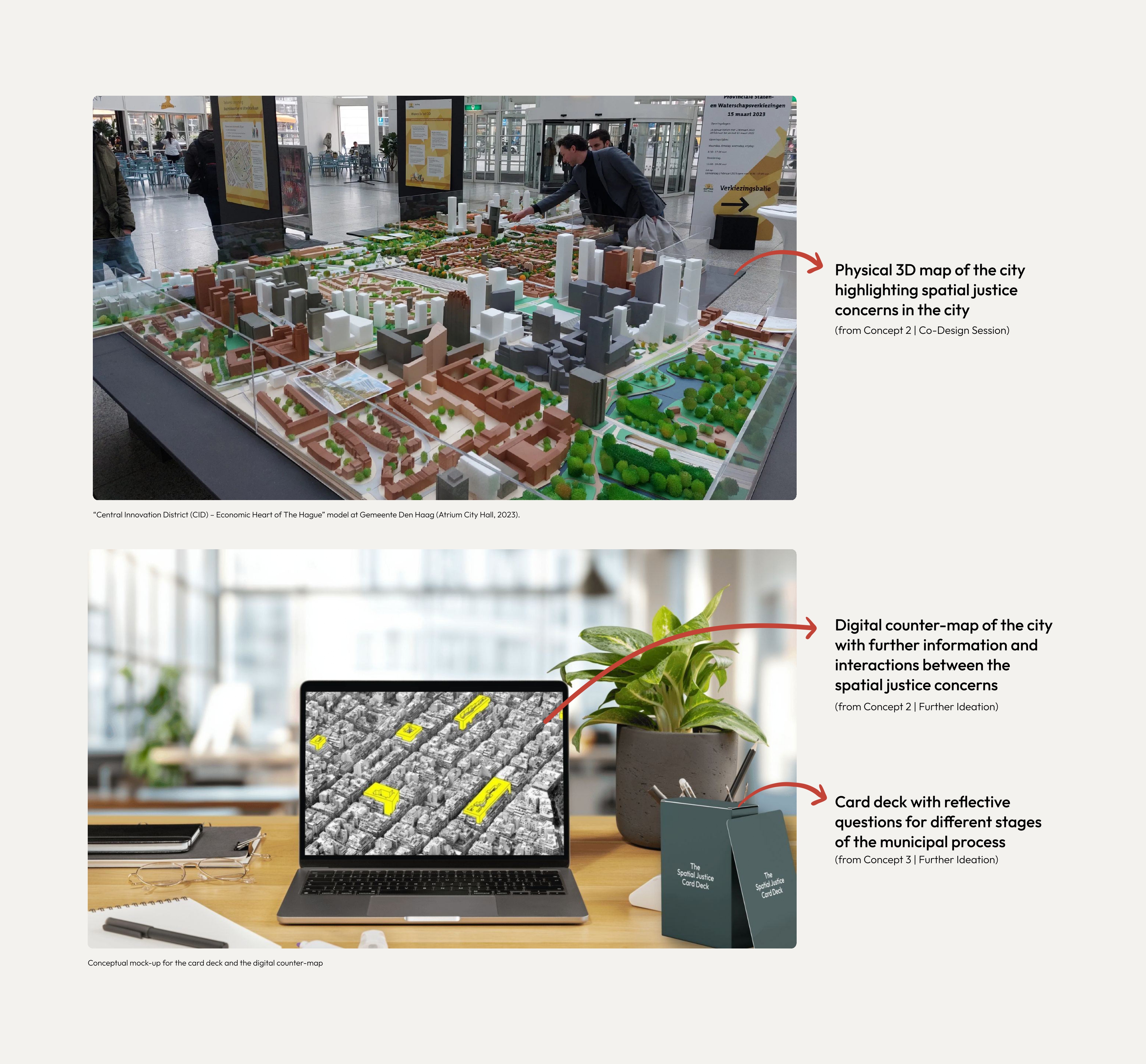

Aligned with the UP2030 Horizon Europe initiative, the project resulted in a practical reflection ecosystem that includes a physical city model, a digital counter-map, and a prompt-based card deck embedded across different planning phases.

✺ Defined key insights and directional concepts through extensive field research;

✺ Translated institutional challenges into actionable design interventions;

✺ Applied Behaviour Change Wheel framework to identify behavioural barriers and enablers;

✺ Collaborated with municipal professionals and field experts (28 in total).

As of 2025, Dutch municipal urban planning and policymaking is increasingly driven by efficiency, housing delivery, and climate-neutrality targets. Within this context, questions of spatial justice — who benefits, who is burdened, and whose voices are included — are often addressed implicitly or inconsistently, making social justice targets become sidelined and faded in the background.

The bottom-up organization Citizen Voice has developed tools to support more just and inclusive planning, including the Spatial Justice Benchmarking Tool and The Spatial Justice Handbook. In testing, these existing resources proved too complex and time-consuming for municipal professionals.

What was missing was not more information or a prescriptive solution, but an accessible entry point: a way to invite reflection on spatial justice that fits within daily workflows and creates space for critical discussion alongside climate and efficiency goals.

Municipal professionals across all regions of the Netherlands, particularly:

A. Policymakers and advisors

B. Project managers

C. Urban planners

These roles play a key role in decision-making and in shaping how climate-neutral goals are implemented, positioning them as central to integrating spatial justice into planning practice.

_page-0001.jpg)

To help make sense of what drives or prevents reflection on spatial justice, I turned to the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW). I used the framework to break down the broad and abstract concept of reflection into workable components. The BCW translates behaviours into variables that can be observed, labelled, and ultimately designed for.

At the core of the BCW is the COM-B model [green], which explains behaviour as the interaction of the following variables:

A. Capability: in this context, refers to people’s psychological or physical ability to reflect;

B. Opportunity: to the environmental and social conditions that enable or constrain reflection;

C. Motivation: to both conscious intentions and more automatic impulses that influence engagement. (Michie et al., 2011).

To deepen the analysis, I also used the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [yellow], which expands COM-B into 14 more specific domains.

The BCW also helped identify realistic types of design interventions [red], while excluding policy change [gray] as outside the scope of this project.

To address Research Question #1, the COM-B Model and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) guided the structure of the ethnographic interviews and the analysis of their results. Interview data was mapped and clustered using affinity mapping, with insights coded as barriers or enablers of reflection on spatial justice.

Research Question #1

What motivates or hinders municipal professionals to consider spatial justice in their planning practices?

Diagram: Enablers of Reflection on Spatial Justice

Enablers are mainly distributed between Social Opportunity (31%) and Reflective Motivation (31%), highlighting the importance of relational dynamics and personal motivation in supporting reflective behaviour. Physical Opportunity (25%) also plays a role, indicating that institutional and environmental conditions can enable reflection when aligned with social and motivational support.

Diagram: Barriers of Reflection on Spatial Justice

Most barriers cluster within Physical Opportunity (45%), pointing to institutional and procedural constraints that limit the ability to engage in reflection. Smaller but notable barriers appear within Reflective Motivation (17%) and Social Opportunity (17%), showing how organizational culture and individual attitudes also shape reflective practice.

Insights from the 7 conducted interviews were translated into 160 data cards and mapped across Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation.

Cards were color-coded to distinguish enablers (purple), barriers (orange), context-dependent factors (blue), and design-related insights (pink).

This step allowed to make the patterns visible. Mapping the data cards within the COM-B framework revealed concentrations, gaps, and imbalances across behavioural domains, clarifying which factors were most and least relevant in the process of considering spatial justice.

While the COM-B mapping provided a structured view of barriers and enablers, it was limited by its predefined categories. To surface more relational and emergent dynamics, an affinity mapping process was used to cluster the 160 data cards based on thematic connections rather than behavioural domains. This resulted in twelve key insights, revealing how reflection is shaped not by isolated factors, but by relationships between teams, tools, and institutional factors (agendas, hierarchies, departmental silos).

_page-0001.jpg)

To address Research Question #2, Research Through Design (RTD) was used to generate insight through designing rather than solely through inquiry.

Four prototypes were developed as provocations to make reflection on spatial justice tangible and discussable, enabling participants to respond, critique, and imagine possibilities through engagement with concrete artifacts. This approach revealed how reflection unfolds within municipal contexts and surfaced needs, values, tensions, and institutional dynamics that are difficult to access through interviews alone.

Research Question #2

What types of design intervention formats are most effective in prompting reflection on spatial justice among municipal professionals?

%201_page-0001.jpg)

A systems map was created to visualize the network of actors and variables influencing reflection on spatial justice within Dutch municipalities. It’s important to acknowledge that the map represents only a partial picture, in reality, municipal decision-making is shaped by many evolving factors beyond the scope of this project.

By triangulating findings across methods and data sources, recurring patterns were identified and validated, ensuring that emerging design requirements were grounded in consistent evidence rather than isolated observations.

The tool(s) developed in this project is intended to complement the existing tools within the Spatial Justice Package—namely, the Handbook and Benchmarking Tool—which already address the intervention functions of Education and Training. By focusing on different functions such as Enablement, Modelling, and Environmental Restructuring , this tool strengthens the overall package, allowing spatial justice to be introduced from multiple lenses and reinforcing change through diverse pathways.

Hence, this project envisions a simple, team-focused tool that helps make spatial justice a natural part of everyday municipal work. By subtly restructuring existing workflows, it creates space for open reflection and shared learning. The tool is designed to model reflective behaviors and enable collaboration and dialogue among team members.

Diagram: Mapping of selected intervention functions (Enablement, Modelling, Environmental Restructuring) [green] to COM-B domains (Social Opportunity, Physical Opportunity, Reflective Motivation) [blue] and their corresponding TDF domains [red]. Showcases the intervention functions in which the existing Handbook and Benchmarking tool fall under [light green].

I conducted two co-design sessions to open up the design process and invite perspectives beyond my own after an intensive phase of individual research. Both sessions were structured as 1.5-hour collaborative workshops with UX Design students and professionals working in impact and experience design, deliberately selected from outside the municipal context to bring fresh, critical, and imaginative viewpoints.

The first session generated playful and experimental ideas, while the second focused on continuity, shared responsibility, and embedding reflection into everyday work structures.

The sessions broadened the design space and brought multiple perspectives into the project—shaping it as a more collective process that reflects the core values of openness and shared responsibility the project itself aims to support.

.png)

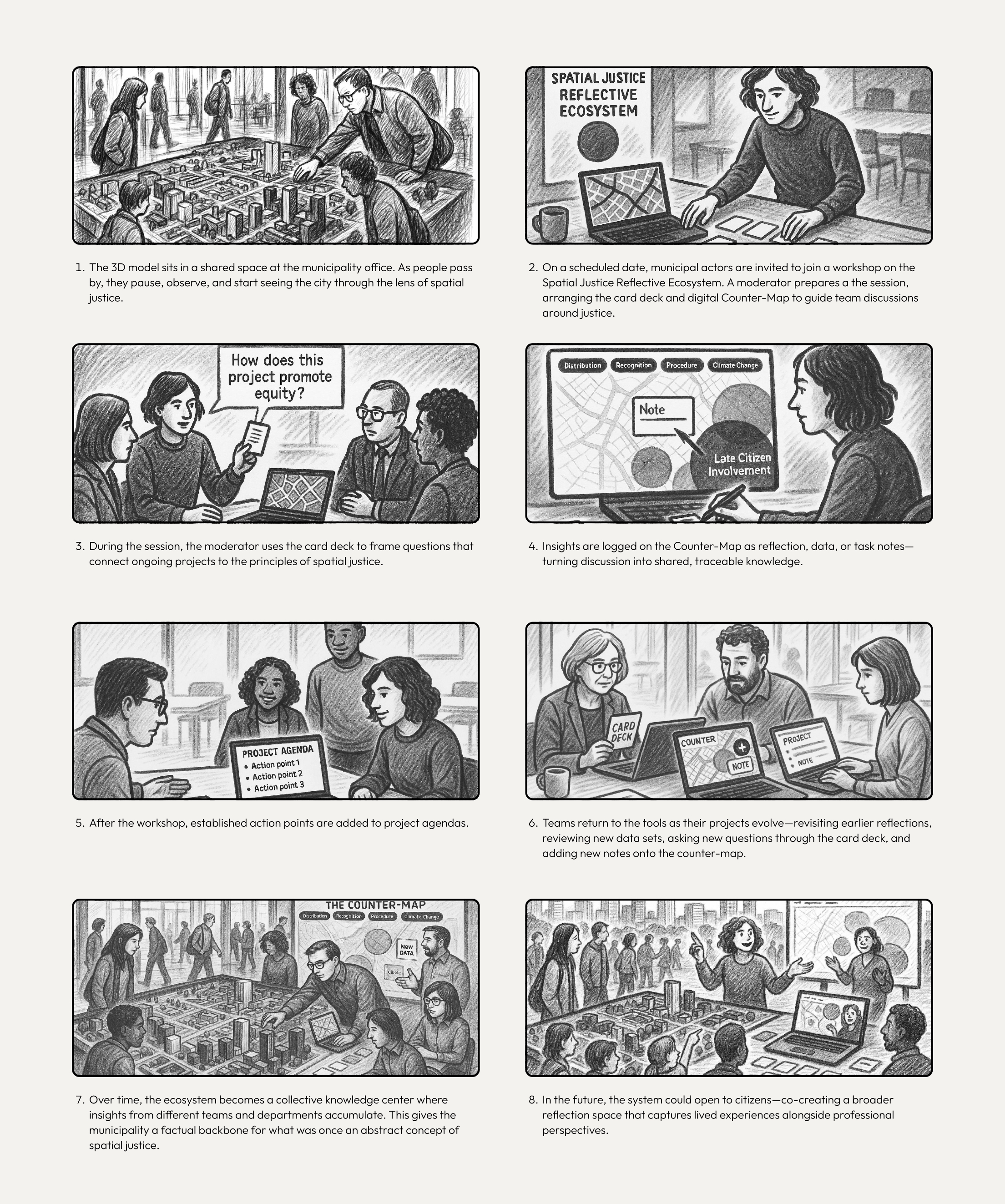

The project began with two co-design sessions, where municipal professionals collectively generated ideas around how reflection on spatial justice could be supported in practice. Rather than selecting a single “best” idea, I developed multiple concepts from these sessions to explore different ways reflection could be embedded into everyday planning work.

Using the COM-B Model and design requirements as a lens, I iteratively refined each concept—mapping ideas, identifying gaps, and testing feasibility through further ideation. This process resulted in three distinct but related concepts, each addressing reflection at a different scale: institutional practices, spatial contexts, and everyday decision-making.

The final concept emerged by synthesizing insights from these explorations, combining what proved most actionable, adaptable, and aligned with existing municipal workflows.

The ecosystem brings together a physical city model, a reflection card deck, and a digital counter-map (that functions as an interactive extension of the physical model).

The physical city model invites professionals to view the city through a spatial justice lens, foregrounding dimensions such as distribution, recognition, and procedural justice rather than conventional planning criteria.

The card deck supports this reframing by prompting conversations at different stages of the municipal process (designing, execution, evaluation, etc.), helping teams reflect and articulate justice-related considerations.

These reflections feed directly into the digital counter-map, where notes, observations, and emerging data can be captured, explored, and translated into concrete follow-up actions.

For the purposes of this project, the physical city model remains at a conceptual level. The reflection card deck and digital counter-map are developed as the primary prototypes.

The card deck initially combines five justice lenses with six project stages, using color-coding and icons to make each card easy to navigate. Each card includes a short explanation and three open-ended questions to prompt discussion, which can be selected and adapted to different contexts. The deck was developed directly in high fidelity to test clarity, structure, and visual hierarchy from the start.

.jpg)

The prototype allows users to explore how spatial justice lenses, data layers, and reflection notes could coexist within a single interface.

The design includes a main city map (based on Google Earth), filters for different justice dimensions, zoom controls, and a side panel for adding reflection, task, or hybrid notes. Color was introduced early to align the Counter-Map with the card deck, using the same justice-based color system.

The prototypes were tested through Think-Aloud sessions with 8 municipal professionals from different regions of the Netherlands, who navigated the low-fidelity Counter-Map and high-fidelity card deck while verbalizing their thoughts in real time.

Feedback was captured using four categories—Likes, Criticisms, Questions, and Ideas—to clearly distinguish what worked and what needed change.

The sessions surfaced recurring issues around clarity and onboarding, data transparency, information overload, navigation, and the need to better reflect how justice issues overlap in practice, directly informing iterations focused on simplification, clearer data ownership, and improved discoverability.

Each card now communicates two layers at once: the justice lens, expressed through color, and the municipal project phase, expressed through iconography and a new card shape. A subtle corner tab changes across the six planning stages, helping users quickly recognize where they are in the process.

The justice lenses were also refined. Power was renamed Procedural to align with the system’s core domains and to avoid confusion with energy infrastructure. Its color was changed from red to a calmer blue. Accessibility was merged into Distribution, and Environmental was reframed as Climate Change, expanding reflection toward ecological justice. This resulted in four final justice lenses.

As the system evolved, the role of a moderator became central. The deck now includes introductory cards—such as How to Use This Deck and What Is Spatial Justice?—to support facilitated sessions. While the deck can be used informally, it is primarily designed for workshops, where it works alongside the Counter-Map and physical city model to create a shared space for reflection and dialogue.

The Counter-Map shifted from being only a note-taking tool to a platform for creating new data. This change reflects the lack of existing municipal data for justice dimensions like procedural and recognition. Users can now create reflection notes, action notes, and data cards, allowing insights that are usually undocumented to become visible and part of the map.

A circular design language keeps the interface light. Filters let users focus on one justice lens at a time, while overlapping areas highlight connections between lenses.

A dedicated Notes section lets users browse all reflection, action, and data notes without relying on the map. Notes can be opened in detail, linked back to their spatial context, and connected to related entries.

%20copy.jpeg)

One of the most important personal reflections from this project was realizing that creating awareness on justice among others is not something a design tool can achieve on its own. Reflection on justice is shaped by much deeper systemic forces—cultural attitudes, institutional structures, and power dynamics that determine what is seen, valued, or ignored. Spatial injustice is rarely an isolated problem, it reflects a network of interconnected dynamics that allow certain behaviours to persist.

As designer Ida Persson writes, “When we design digital experiences, products, or services, we're not just creating things—we' re influencing lives, cultures, and behaviours. This is a privilege to design and something we should not take lightly.” This project reminded me of that responsibility.

Design alone cannot dismantle systems of injustice, but it can help make them visible, tangible, and discussable. For me, this project represents a shift in how I understand design—not as a way to fix problems, but as a way to see them more clearly. I encourage readers to also see it as a starting point rather than an endpoint : an attempt to make spatial justice visible in everyday work—and an invitation for others to take it further.

~ Daniella de Rijke Rodríguez, October 2025.

Focused on designing a digital knowledge center that helps diverse audiences navigate complex ecological themes without compromising their experience.